Building Your Sonic Brand

By 2018, the federal government will mandate that all new electric cars make an audible sound. The ostensible reason is to assist blind people — and the rest of us — echolocate the increasing number of silent 2-ton masses rolling down our streets. The government’s prescriptions are precise, with specs about volume and decibel changes to indicate shifts in speed. But within those constraints, the car companies saw a novel opportunity: The regulations do not necessitate mimicking the rumble of a combustion engine. “With electric cars,” said Connor Moore, a 34-year-old San Francisco audio designer, “you can create the sound from scratch.”

Moore led me into his studio, located on Shotwell Street in the Mission District — one room in a building crowded with set designers, videographers, and art directors. Along one wall are Moore’s two skateboards and a basketball, and along another, a fleet of Gibson and Epiphone guitars, even a ronroco, a kind of Bolivian ukulele. With his clean-cut, near-Gosling good looks, Moore is almost manic when he talks about designing a car sound from the ground up — “It’s something that’s never been done before,” he told me.

Think of the telephone’s ring, once actual bells and clappers, shifting into an array of fully composed, harmonically appealing digital ring tones. Electric cars will make that same transition, including being branded by car model. We will know that it’s a Nissan Leaf; or an Uber self-driving car; or a Google, Apple, or Microsoft car before it even pulls into view. These new car sounds might subtly allude to the old internal combustion engine but in that hat-tip way that HBO’s station identification refers to the static of changing channels on an old Magnavox.

These sounds will trigger emotional reactions in us as we hear them come down the street. We will be able to sense and feel that a new car is coming, one that doesn’t directly burn fossil fuels, a car that prowls rather than chugs. The artifice of that sound will tell us a story about a culture’s escape from a 100,000-year history of dependence on fire, a story that new visual contours or obscure color palettes can’t communicate at all. No aspect of the new electric cars will arguably do more to render the combustion engine obsolete as quickly as these new multilayered sounds — possibly turning the huffing clunkers out there into the next decade’s giant cathode-ray TV sets now orphaned on the curbs of America’s cities.

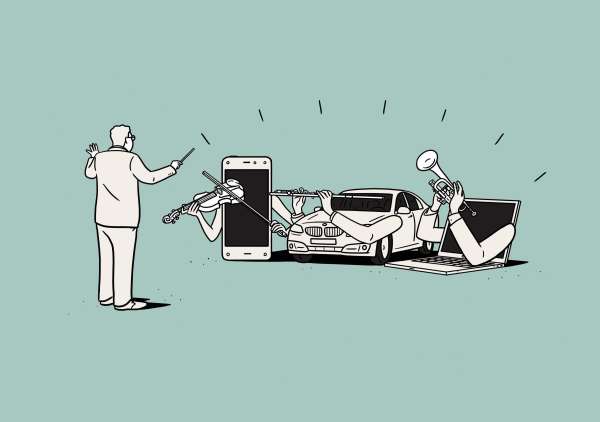

The few seconds of music Connor Moore writes is called sonic branding, the composition of audio with some core functionality, product association, and aesthetic appeal. In theory, this kind of minimalist marketing dates all the way back to the beginning of recorded sound with MGM’s lion roar in the running for earliest, if not longest-lasting example. Sonic branding involves stand-alone sounds, like NBC’s three-note signature or United Airlines’ use of the most familiar measures of “Rhapsody in Blue.” These distilled riffs are meant to build an aural association with a product to create a Pavlovian sense of loyalty and expectation. Consider how primed you are to see great television when you hear HBO’s staticky hash resolve into that choral crescendo — even if what follows is an episode of Dane Cook’s Tourgasm.

Before composing music to build brand identification, Moore was, like everybody, in a band. He also did some DJing while he studied ethnomusicology at the University of Kansas. After graduating, he stumbled into a gig creating music on a Samsung project, and the work was not at all what he expected. “My own knowledge of this was simply music for advertising,” he said, but what he discovered instead were “people crafting sound experiences for products and brands.” Moore found that he liked thinking conceptually about a product and then translating that notion into music, especially because it involved immersion “in the product and thinking about the end user and what makes consumers feel a certain way — and you had to think about it before you start composing, and that seemed unique.”

While sonic branding is narrowly defined as music composed for a specific product or company, the larger field Moore works in is technically known as sound design, a concept that extends the notion of our fabricated soundscape to include video games and movies, even the selection of musical tempos in hotel lobbies that alter one’s sense of how pleasant one’s stay has been. These related pursuits overlap, and the terms can get confusing: acoustic branding, sonic mnemonics, music branding, or even sogos (sound logos) and mogos (music logos). It all winds up in a spirographic Venn diagram.

A lot of this work originates with advertising firms, where the exploding number of companies have the kind of names that you might expect for sogos creators — Audiobrain, Rumblefish, MassiveMusic, NeuroPop. There are so many such outfits that they have their own professional organization: the Audio Branding Academy, which holds a grand pageant every year that bestows the coveted Audio Branding Award. The language these companies speak sometimes suffers from the eager hype and love of forced portmanteaus we’ve come to expect from a field built around salesmanship. Some straight-facedly call this emerging world the mogoscape and speak of the wonders of audvertising. Not a typo: audvertising. Sound, they argue, is more direct and emotional than visual imagery because, as sonic brander Julian Treasure puts it, humans have no earlids. Earlids.

Breathless salesmanship aside, the cumulative effect of these oversold pursuits is an admirable, if arcane, kind of beauty. The old world of blaring radio alarms, car-theft sirens, and braying appliances is in full retreat. The customized alerts of your cellphone are just the beginning. A new world around us is being scored.

Joel Beckerman is one of the grand theorists of sonic branding. “Sounds trigger familiarity,” he told me, “but they also trigger positivity memory.” Beckerman, too, began life in a rock band, but after the inevitable breakup, he stayed with music, composing for commercials. Eventually, jingles faded away, and branded sound focused into these pointillist riffs of association. Now 53 years old, Beckerman has emerged as one of the pioneer practitioners at the firm he founded, Man Made Music (in Burbank and New York) and is the author of the central text, The Sonic Boom, which not only makes the case for sound as salesman but that its nuances can reach far outside the recording studio.

Fajitas, Beckerman writes, were merely a decent-selling dish that went supernova as a middle-class entree after Chili’s focused its presentation on the loud sizzle of the dish emerging from the kitchen, a sound that figured into all its key advertising. Spend enough time pondering the nuances of sonic branding, and you come to appreciate the pure genius of the letter z in the word Prozac.

For BMW, maintaining consistent acoustic character throughout its fleet is an executive job description. BMW doors close with a clunk that must be in concert with the acoustics of the rest of the car, like the notes produced by the exhaust or the hum of the window motor. Most drivers of BMW’s M5, for instance, are probably unaware that the engine sound they hear when driving is a replication piped to the interior of the car via the speakers of the sound system.

When Amazon was creating the Fire Phone, it called upon Moore to create a full set of branded chimes for the phone. In his studio, he played a series of gorgeous, full chords. They were ring tones, alerts, various notifications — about 60 altogether. There was something symphonic at work here, a series of arrangements that were related and themed. Composing these sounds was labor (it consumed about a year and a half of Moore’s life), and I could detect the nuances. For instance, the Fire Phone’s primary ring tone — pulse/pulse, pause, pulse/pulse — was rhythmically quoting the original landline ring.

Most of us are unaware of just how much conceptual intrigue goes into the few measures of any of these phrases and harmonics, until you think of how many of these sounds you can hear in your head before you click on Google: Intel’s bongs, State Farm’s phrase, Pillsbury Doughboy’s giggle, iPhone’s default ring, Snapple’s popping lid, THX’s glissando, Alka-Seltzer’s fizz, the Windows XP chime, or T-Mobile’s five-note tone.

“All brands exist on multiplatforms now,” Beckerman said, so that the whole point of a sonic brand is to create a sound that, first, is appropriate to the thing but then to vary it and deploy it in all kinds of locations — in TV ads, on hold with customers, on cellphones, in radio spots, as a browser alert.

Getting an object or an action lined up with the right sound is still more art than science, but it is clear when it fails, resulting in the clangorous tunes or weird chirps that still litter our soundscape, what Beckerman calls sonic trash. He is fond of telling the story of SunChips, which for a while came in a crunchy bag that managed to be louder than the chips, so annoyingly loud that Facebook still has a page headed “Sorry But I Can’t Hear You Over This SunChips Bag.” When a consumer reporter on TV proved that crumpling the bag produced 100 decibels, while a subway train clocked in at 94, Frito-Lay killed that version.

The renaissance of ambient sound parallels the rising concern in the late 20th century with noise pollution — the sudden upsurge in the tinnitus-inducing wails of car alarms and the tooth-loosening ingestions of sanitation trucks. Some 40 years ago, the author R. Murray Schafer described our soundscape as the “apex of vulgarity” and added that “many experts have predicted universal deafness as the ultimate consequence unless the problem can be brought quickly under control.” Schafer presciently called for the “tuning of the world.” The initial concerns of noise pollution only addressed the problem of big sounds clamoring in our city streets. Later, other obtrusive and hideous pitches breached a more intimate frontier — us. The technological efficiencies of many of our devices have positioned them physically near our bodies, whether we are in our homes, cars, offices, or out on foot.

For the longest time — in the late ’80s, early ’90s — the noise that greeted you when you booted up your Macintosh was a noxious beep. Musicologically speaking, it was a tritone, an unpleasant combination of notes known as an augmented fourth. In the Middle Ages, it was called the Devil’s Interval, and the anxiety and melancholy it was alleged to induce in any listener caused the Catholic Church to ban its performance. The Devil’s Interval is the opening notes you hear in the title track of the album Black Sabbath.

No one has written a definitive history of the computer beep, but it’s as layered a story and as worthy of a book as, say, cod. The beep’s origin isn’t clear, but a question to ask is whether the beep came from one of those ancient UNIVACs or whether science fiction didn’t create it in our movies and TV shows. (Think of the beeps that populated the bridge aboard the original Starship Enterprise or of George Lucas’s questionable choice — that R2-D2 speaks exclusively in the idiom of medical pagers.)

The story of how Macintosh started to transform those beeps into less harsh tones mirrors the story of sonic branding itself. The Beethoven of the sweeter, lusher computers is Jim Reekes, an Apple engineer, who came up with the unfolding harmonic that now turns on a Macintosh computer. He’s also responsible for many of the other peppy cadences that signaled various keystrokes — the duck quack, the camera click indicating a screenshot.

These tones arrived not without some difficulty. At the time of these recompositions, Apple was being sued by the Beatles for its use of the word apple. Out of pique, Reekes wanted to name one of his new sounds “Let It Beep,” a pun that works on so many levels, it’s nearly justifiable. But he knew the lawyers would object, so, instead, he wrote out a made-up word that looked slyly Japanese: sosumi. This cleared the lawyers, who only later realized that the word is pronounced, “So sue me.” (Note to audvertisers: That’s how you coin a word.)

The creation of the Mac chime more or less inaugurates the golden age of composed interstitial sound — the coming Schafer utopia into which we are now heading. Around the time Apple turned to Reekes, Microsoft hired Brian Eno to score the opening notes for its operating system. The difference is classic. Apple’s chime is elegant, optimistic, commencing. Eno’s score is like a symphony reduced to three seconds — rolling through at least three different movements resulting in the perfect Microsoft intonation: fussy, narrative, involved. Microsoft has since recast its sound to something more direct and effortless, a sonic brand in other words.

The tiny riffs of sound that Reekes and Moore and Beckerman have produced operate in our ears, when done well, in subconscious ways. Beckerman has a cognitive scientist on staff who collaborates with them to generate sounds that involve “low cognitive load.” Think of the tones that signal the few final seconds of a green walk light at an intersection. Next time, watch how people don’t bother to look but simply pick up their step when those sounds chime. That’s what Beckerman means by low cognitive load: smartly scored bolts of sound that communicate to us below the level of conscious thought or visual confirmation.

While some sounds can convey specific meaning, most of these communications are largely subjective. Still, categorizing these connotations is underway. Beckerman has compiled playlists of compositions that, according to his science, can alter one’s mood from optimistic to creative to calming. There already exists Pandora Media’s grand undertaking, the Music Genome Project, which reduces all music to some 450 attributes, intended to create “a deeply detailed hand-built musical taxonomy” — to do for sound what, say, Linnaeus did for the animal and plant kingdoms. Meanwhile, numerous cognitive studies reveal unusual connections between sound and reality. Classical music, for instance, in a wine store leads to high sales of pricier bottles, and it also seems to make certain wines taste better.

Dig into this science far enough, and the speculation can get a little hairy. Sonic theorist Julian Treasure has opined that hearing, unlike the directed and piercing gaze of the visual, is a “more feminine” sense because it is “passive, receiving, always open.” (I think I will back out of this paragraph, very slowly.)

Undoubtedly, there’s more work to be done in mapping this sonic hinterland between purely functional sound and the looser connections of tone and mood. This, I suspect, will always be fertile terrain for salesmen, conference speakers, and bad neologists. But composing unrepellent sound as a way of communicating with our machines already appears to be moving on to new territory.

Think of the next phase as a kind of crawling-out-of-the-sea-onto-land moment for our species’ relationship to technology. “When I first started doing this,” Moore said, “it was all about touching a product and the product having a sound.” The next level of interaction, he said, would more likely involve pure sound — depending on how the next generation of technological improvements unfolds.

Moore said that he is getting more and more queries about creating branded sounds for robots — especially robotic home companions, like Jibo or Echo. These are nearly sentient appliances that are marketed as “friendly, helpful, and intelligent” (dogs, be warned) and sold as “social robots.” Almost certainly, we will interact with them in ways comparable to what is developing inside the newest cars.

Obviously, the least fatal way to communicate via Bluetooth or even a heads-up display in a moving car is through sound. Trying to coordinate those communications so that they happen below the surface of thought, Moore said, is the goal. He described how new compositions for the GPS in a car might not talk directly to the driver anymore, but instead “produce tiny pings on the left side of the car to turn left or on the right side to turn right and utilize the stereo field” in order to “give the driver information without having to look at a device and without screaming, ‘Turn right!’”

Beckerman said something similar about the home. “Technology is so interwoven into our lives that we now have a lot of computers in our houses,” he said, but “we have to break the tyranny of the screen in terms of how we connect. I don’t know about you, but I don’t want a hundred screens in my house as I start building my connected home.”

The English language might still be used by our future robot/car/domicile overlords, Beckerman said, but rarely. Our brains have to pause, listen, and comprehend when we hear spoken words. Because language involves a high cognitive load, such interactions will be reserved for critical situations.

With similar thinking, Moore has been scoring a variety of possible meanings — “Hello.” “I’m stressed.” “Looking good.” “Way to go.” “What time is it?” — to be conveyed by musical intonation rather than outright vocabulary. “They are, in fact, sounds,” Moore said, “and what I am doing is modeling them on human speech and using linguistic ideas to create this sound set — challenging but really cool.”

Sonic branders talk about our interactions with our devices as if what they are composing is not so much music as sonic linguistics. Given the near future of a communication singularity among our houses, cars, robots, and our bodies, technology will move beyond the necessity of touching and toward something that altogether resembles a new language. “Composing within that voice experience,” Moore said, “is going to be huge.” Still, that experience will be largely corporate (and, soon enough, annoyingly so). These emerging languages will be associated with specific products or companies. They will be branded. The time is not far off when we will hear it in the air and be able to recognize something as spoken in an Amazon patois, a Cartier Mid-Atlantic, or a Walmart drawl.